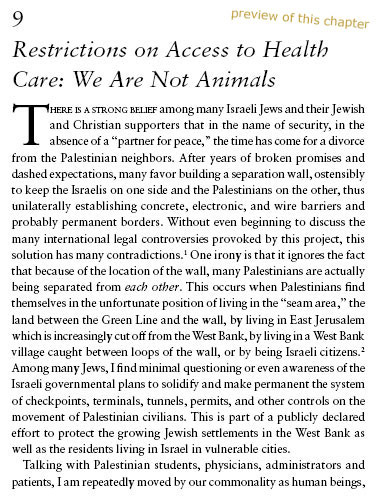

This poster that I saw in the PMRS office in Jenin, West Bank, showing an Israeli tank confronting a Red Crescent ambulance at a checkpoint, captured the difficulties of trying to deliver health care in the Occupied Territories.

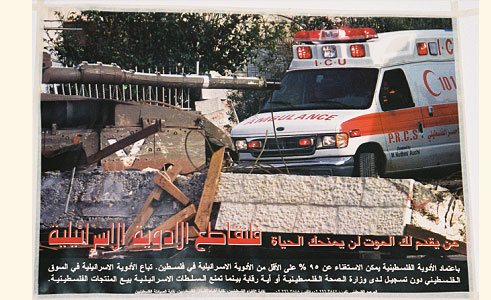

We were repeatedly impressed with the problem of inadequate and unpredictable access to health care in the West Bank. In Abu Dis, a suburb of East Jerusalem, the separation wall cuts through neighborhoods, blocking streets, dividing families and friends, and disrupting daily activities, education, and health care.

In 2004 and 2005, parts of the wall were completed while other segments had breaks where Palestinians climbed through to cross the city, heaving packages, babies, and each other over the concrete blocks.

We saw older people, infants, wheelbarrows, handed over the break in the wall as Palestinians attempted to shop, go to work, school, and conduct normal daily life activities.

With all the disruption and daily inconvenience, when the wall is completed, these breaks will be closed off and the restrictions of movement will be even greater. One medical student talked about patients unable to get to the hospital in East Jerusalem while hospital wards remained empty and the medical personnel waited without work.

This view of Abu Dis from the Mount of Olives reveals the impact of the

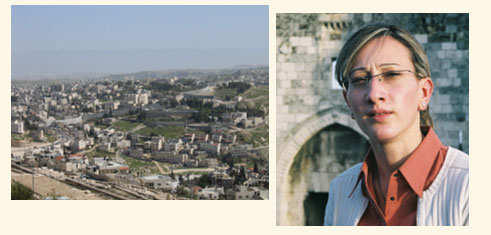

separation wall snaking through the neighborhood, isolating the university campus. ST, a medical student, talked about the impact of the wall on her own life and medical education

On the Mount of Olives, ST and Seema Jilani overlooked the walled Old City, the dazzling gold Dome of the Rock, fountains and gardens of the Noble Sanctuary or Temple Mount, and Al Aqsa Mosque, an area central to the three Abrahamic religions.

ST and some of the delegates met at the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem, exploring the city and its complicated history. ST discussed her years of experience with dialogue and peace groups involving Jewish Israelis and Palestinians and her involvement with Seeds of Peace in the US.

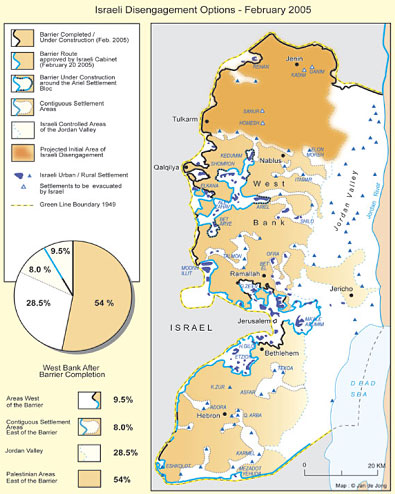

This is a map of the West Bank showing the location of the separation wall as of February 2005. Much of the wall is in the West Bank, rather than on the Green Line.

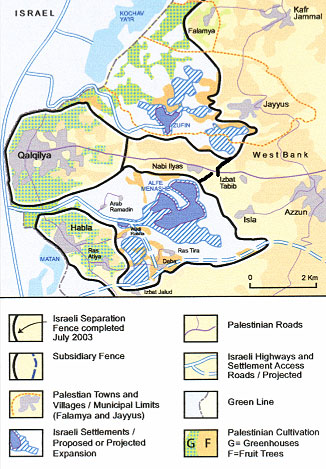

This is a map detail showing Qalqilya, completely surrounded by the separation wall, by pass roads, and Israeli settlements north and south. Residents exit through one checkpoint through the neck of the bottle into the West Bank.

We visited Qalqilya, met Palestinian children and their families, and learned of the devastating consequences of the wall to the local economy.

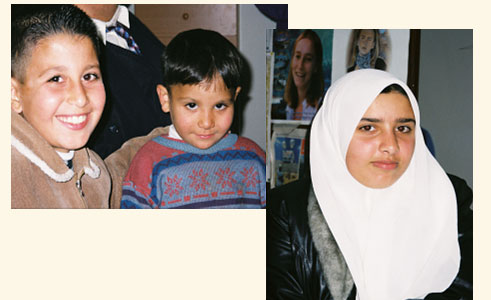

Palestinian children from Qalqilya, a city totally surrounded by the separation wall, live in a virtual prison. For most, their only contact with Israelis is through the military.

The residents of Qalqilya once had a brisk commercial relationship with

Israelis. Now the city has an estimated 70% unemployment and a large

percentage of the population relies on food aid.

In Qalqilya, Souad Hashim, a guide working with PMRS, explained the

crippling impact of the separation wall on the people and the agricultural

and commercial economy.

The concrete wall in Qalqilya is 26 feet high and includes imposing guard towers, an adjacent military road, and a no-man’s-land, sometimes with trenches and barbed wire.

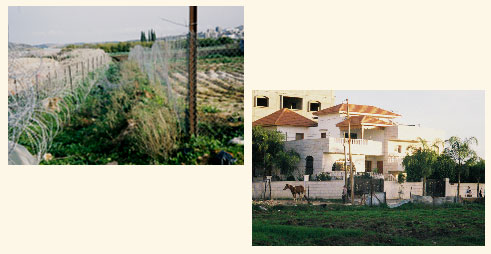

Israelis claim the separation wall is necessary to prevent suicide bombers from reaching Israel. The imposing wall has had an enormously destructive impact on the lives of most Palestinians. On the left are hot houses adjacent to the wall, which bisects Palestinian owned land.

We tried to understand the impact of the wall on the residents. On the left, a boy herds the family’s sheep along the military road, which is dangerous and oppressive. On the right is a new school that was built before the wall and is now adjacent to it. The wall actually blocks Qalqilya’s view of the sunset.

We approached one of the gates with Ms. Hashim and her daughter. The gates are opened erratically twice a day for farmers with difficult-to-obtain permits to reach their fields beyond the wall.

Ms. Hashim discussed the inconvenience and unreliability of access through the gates and noted that the one pictured on the right is never opened.

Ms. Hashim’s daughter entertained herself by drawing Stars of David and placing an X through each one. An Israeli military vehicle pulled up and a young woman soldier inquired as to our safety, incredulous that we were voluntarily inside the city.

Along the wall, we saw barbed wire coiled into local gardens. A beautiful home was abandoned when the wall was built adjacent to the building, viewed on the right from the no-man’s-land.

On the left, a farmer told us of the devastating consequences of the wall to his access to his land. On the right is a view from the wall, across the military access road, no-man’s land, to the homes and buildings of Qalqilya.

Qalqilya lies eleven miles from Tel Aviv and nine miles from Netanya. Just beyond the walled city lies a Jewish settlement with its characteristic red roofs and easy access to Israel.

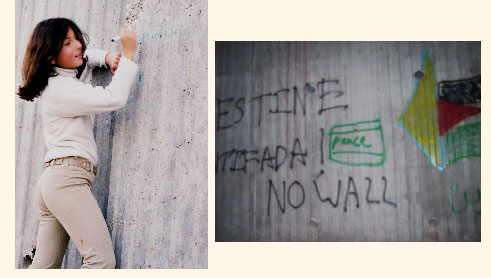

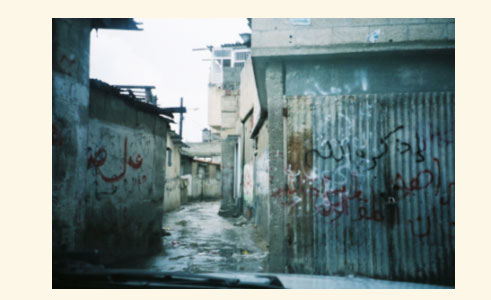

The wall is covered with painful and evocative graffiti, a few words by Ms. Hashim’s young daughter and most from local and international protesters.

As a Jewish delegation, with our own recent history of ghettoization and persecution, the angry, ugly parallels etched in the graffiti were painful and provocative, but understandable.

An Israeli soldier shot warning shots over our heads to express his displeasure at our visit. The area around the wall is considered a closed military zone by the Israeli government.

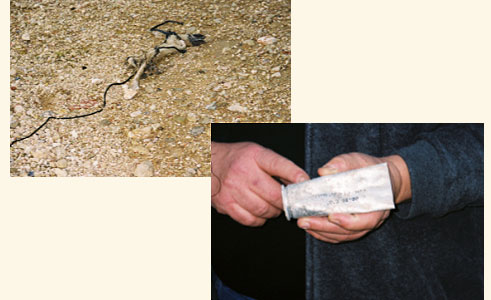

We found slingshots and spent casings on the military road adjacent to the wall, a testament to the ongoing Palestinian resistance and Israeli military presence.

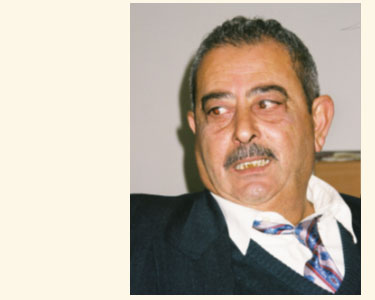

We met with Dr. Hussein Shanti, a family doctor living in Qalqilya with a private office beyond the wall. Now he sleeps in his office, seeing emergencies during the night, and then attempts the unpredictable return home to work in a clinic in the city and see his family by day.

Dr. Shanti and a number of his children arrived at our apartment in Qalqilya, each carrying a blanket to protect us against the cold night. The children were soon engaged in our computer games and the chocolate and baseball caps we offered as gifts.

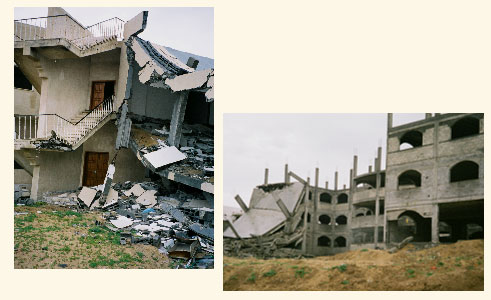

In 2005, we visited Dr. Izzeldin Abuelaish, an obstetrician-gynecologist, who was born and raised with eight siblings in the Jabalya Refugee Camp, (on right), Gaza Strip.

Dr. Abuelaish showed us his family home in the Jabalya Refugee Camp. His parents were deported to Gaza from a former Palestinian village called Huj in 1948. The family of nine children and two adults lived in a two room house without electricity or running water. The home was demolished once by Israeli forces to widen the road in the camp to accommodate tanks. Dr. Abuelaish attended UNRWA schools and received a scholarship to study medicine in Cairo.

Dr. Abuelaish showed us the northern Gaza Strip which was devastated by an Israeli incursion in 2004. We saw a Bedouin camp in the distance (on left), with a mother and child living in extreme poverty (on right).

We talked with a Bedouin father living in temporary housing after the 2004

incursion. The terrible state of his teeth and gums is a marker for the

inadequate health care and poverty that is prevalent in this area.

Dr. Abuelaish showed us the devastated area, northern Gaza, post Israeli incursion. An estimated 75% of Gazans are living in poverty after years of Israeli incursions, mismanagement by the Palestinian Authority, and military conflict within the society.

We met teenage boys in northern Gaza. Young people have limited educational opportunities in Gaza. They are unable to travel legally to universities in the West Bank and have difficulties crossing south into Egypt. On the right, looking north towards the border with Israel, is the industrial area and open pits of sewerage.

We toured a Palestinian Medical Relief Society clinic in northern Gaza. A local

physician demonstrated bullet holes from the 2004 Israeli incursions.

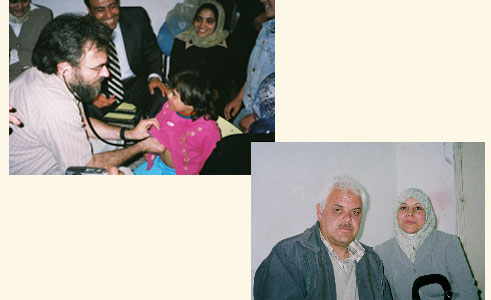

Dr. Abuelaish invited us to his family home, a brother on each floor, on the edge of the Jabalya Refugee Camp. On the right is his wife and two older daughters who have attended the Creativity Peace Camp in New Mexico.

We met with local children and the director of the El Morshed Educational Social Society on the left, and then entered the waiting room on the right, filled mostly with mothers and children waiting to see the American doctors.

Dr. Meyers examined a child with Down’s syndrome and found a lack of needed medical facilities for this developmentally disabled child, while Dr. Abuelaish and I interviewed infertility patients in an adjoining room.

Most of the infertility patients at El Morshed had years of difficulties, inadequate and difficult to comprehend workups, and a burning desperation to conceive as they live in a society that values large families and many sons.

We also evaluated a family from the Jabalya Refugee Camp who sought consultation with the American expert regarding their two daughters are congenital hormonal disorder which would have been challenging in a first world setting but were near impossible here.