One of the greatest casualties of the ongoing war on Gaza is childhood. The Gaza Community Mental Health Program Deir al Balah Community Center has an extraordinary exhibit of post-war children’s drawings that gives us a window into the loss of the sense of order and safety that comes when one of our smart bombs lands in your bedroom.

The drawings are breathtakingly painful and simple in their honesty, a child’s view of a world gone horribly wrong:

The delegates stare, take photos and are pulled into each drawing; some of us are weeping, some of us just floating in a sea of societal trauma.

Children chained together in front of a soldier with a whip, families lined up in front of a tank, bombers shooting birds out of the sky, pools of blood, lots of blood, bloody circles on people’s chests, over and over again, fallen trees, smiling men in kaffiyas waving the Palestinian flag, a dove holding a circle of wounded people facing a missile, apache helicopters dropping bombs, walls crumbling and crumbling, neatly drawn piles of rubble, fires, ambulances, more dead people, doves the color of the flag dripping with blood, lots of blood, naval boats bombing from the sea, tanks, planes, and soldiers with prominent stars of David, curled barbed wire, missiles landing on vegetable trucks, more tanks and planes and fire and people lying on the ground bleeding, four boys on a beach flying kites with bombs falling on their heads, a heart with the word Gaza written across it in black, white, green and red, split in half, pierced by two missiles bearing the Star of David.

Not only am I appalled by what these children have witnessed, but I am sickened (once again) that in this world, the Star of David is synonymous with military violence, grief, and death.

Dr. A. the only female psychiatrist in Gaza, explains to us that the children are six to 14 years of age and were involved in art therapy workshops to address their posttraumatic stress disorders after the war. She reminds us that behind every picture is a story and she is filled with these stories. Most of the children lived along the border towns. One of their fathers picked up a stranger looking for a ride and both were killed, he has two daughters and is also related to A. The targeted assassination hit the wrong guy. One of the children wrote on his/her drawing: “So if you killed my child, you think you are strong?” Another: “I want to live in peace.” She admits, “I cried a lot during their therapy.” Another family, the grandmother was killed, the family was running in the street to the UNRWA school, rockets and bombs flying, a sister and a chicken were killed in front of the child and (s)he did not respond. “They get used to the situation. A six year old witnessed three wars, this is normal. They get strength.”

She has treated 34 children and 24 are cured of their symptoms. She has a collection of 300 pictures and we sit with her piles of paper. She tells us of Mohammed, an angry 11 year old, aggressive gun play, doing poorly in school. He drew a child in bed, black shirt, jeans, blood on his chest. He told her, “’This is Ahmad [his friend]. I saw him on TV he was killed.’ Now he is cured, at the last session he was playing with toys” and doing well at school. “The stories are overwhelming. They taught me how to be strong.” A very gentle soul, A. started as a general practitioner but was drawn to psychiatry, trained at GCMHP and feels that she is called to work with children on these challenging issues. She meditates to reduce stress and feels that “in Gaza there are a lot of opportunities to support people….I let go of hate. I have so much love. I love Moses. I love Jewish.”

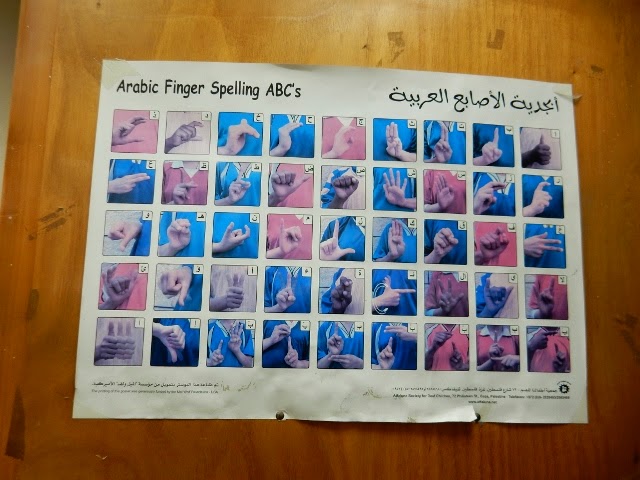

Our next stop is at the extraordinary Atfaluna Society for Deaf Children, a Palestinian NGO for Deaf Children in Gaza City working in the field of deaf education, vocational and community training since 1992. Atfaluna is Arabic for “our children” and the center focuses on academic education for deaf students who were traditionally hidden away by their families and treated as mentally defective, and the building of human and vocational skills to prepare students for productive and independent lives. They are famous for their gorgeous embroidery and furniture making program and we thoroughly investigate their craft store and make our contribution to the Palestinian economy and the school. They report a dramatic increase in hearing loss in babies born since the last war. A scientific study needs to be done, urgently I might say.

The NAWA for Culture and Arts Association is a phenomenal children’s art and culture program led by Reema Abu Jabir, a visionary force of nature. She is the kind of person that makes me actually want to be a child in Gaza! Started after the 2014 war, Reema created a center to support and empower young Palestinians using traditional culture and arts, directed towards families in the Deir El Balah area. They provide psycho-social support, early childhood education, professional development for educators, and preservation of Palestinian culture. As we enter, there is an immediate sense of calm; they chose the wall colors “to mimic a mother’s tummy” and each room is bordered in a traditional red pattern evoking palm trees. We visit the children’s library (there are no electronic or internet connections for the children per Reema), look at drawings and poetry and sayings: The famous political cartoon character, Handala, “bitter fruit,” with his back to the world, Darwish and other poets, “You can’t find the sun in a closed room.” At the end of the morning and evening shifts, the children gather in a closing circle, chanting phrases like: “There is no sun under the sun except the light of our hearts.” “We need little things in life and if we are happy we will be kings.” “You and me, he and she, we will all be different. There is a difference between him and her though our lives are beautiful like flowers.” The children do increasingly complex rhythmic movements to the chanting and singing, engaging their minds, hearts and bodies fully. (I cannot resist pointing out how monumentally inaccurate it is to say that Palestinians teach their children to hate…just want this on the record.)

Reema explains that the children participate in much of the building with recycled wood, there is a lively art room, a family pays 10 shekels a year. Reema believes in setting clear rules (these are children whose lives have turned upside down) and providing a clean, safe space, and at the same time, this center is a home; she is addressed as Auntie. The center is open for all citizens, not just refugees. We wonder how she keeps her focus and her strength, so much has been accomplished in such a short time. She admits that she does get depressed and angry, fights with her friends, shouting and then apologizing the next day. She goes to the sea to relax.

Reema’s next dream involves turning a 1700 year old monastery with a mosque downstairs in Deir Balah into a garden and children’s library. We drive to the ruin which is in a very poor area and she is obviously animated and planning for the future. The children have cleaned the ancient stones and arches, the Ministry of Tourism has signed an agreement, money for restoration is being collected, and she is in contact with UNESCO for the restoration. The major difficulty is the lack of cement in Gaza which made donors a bit hesitant. Reema says defiantly, “I am stubborn like a donkey, this is from my father’s side.” The monastery is a mosque and a monastery and thus a reflection of the message of tolerance at the arts center. Reema complains that UNESCO asked her to get the building materials for the restoration. “Don’t ask me to get cement for Gaza!” And you just know that she will make this incredible project happen.

We chat with the cab driver on our way back to the guest house. He says, “Welcome to Gaza! Take me in your suitcase to America!”