M. has been a psychologist at the Treatment and Rehabilitation Center for Victims of Torture for six years. After a lively supervision session with four other psychologists, we walk through the jostling streets of Ramallah and pay three-and-a-half shekels for a service to the Jalazone Refugee Camp just north of the city. The camp is crowded into a quarter of a square kilometer, some 15,000 to 20,000 people descended from 36 villages in the Lydda/Ramleh area pre-1948. UNRWA lists its major challenges as a lack of a sewer system and overcrowded schools. The UNRWA school was renovated in 2014 after years of double shifts. On the radio, a man sings verses of the Quran and Mohammed urges me to “Just listen, the Quran teaches peace, just listen.”

At a rotary near the Jewish settlement of Bet El, there are burned/blackened areas, the sites of frequent conflicts between stone throwing Palestinian young men, burning tires, and heavily armed IDF soldiers. We reach a concrete road block with two Israeli soldiers, M. informs me we are 20 seconds from Jalazone, but we have to make a wide detour on a poorly maintained, narrow, bumpy, circuitous road, the traffic slows to a crawl. M. talks of a cousin in Omaha, his wedding in July, of the poverty in the camp, and the strength of the people. He is coming to make several home visits.

Center of Jalazone refugee camp

Center of Jalazone refugee camp

Jalazone refugee camp

Jalazone refugee camp

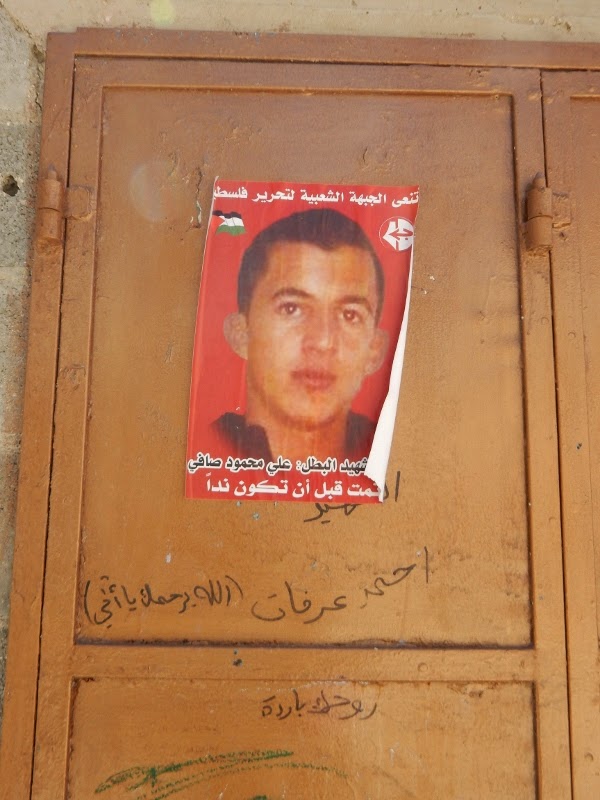

First we stop for what seems to be a slow paced schmooze at the Rehabilitation Center for Disabled Children, checking in with the lively director, chatting with two patients. I tour the facility, the small children’s arts and crafts and play therapy center and a larger area for physical therapy. M. has run weekly group therapy sessions here, but all the talk is about the 20 year old young man who was shot dead in the street one week ago, throwing stones, can M. add his family to his case list? His family is very poor. A poster on the wall features a man crouched in a bottle and the words: Thirst for Freedom. A smart phone rings with the same jingle as mine, a staff person works at a computer, chain smoking. Lots of people smoking here, men and women.

Rehabilitation Center, physical therapy unit, Jalazone refugee camp

Rehabilitation Center, physical therapy unit, Jalazone refugee camp

We head out to the first family and I am struck by the bleakness of the camp, all chalky concrete and winding streets, no green space, many martyrs posters, a rare scrawny plant, houses against houses. M. is well-known, he laughs when I say that he is the camp psychologist and I can see he is enjoying his rock star status. He greets a number of former clients, ex-detainees, mothers of detainees, there is much embracing and strong handshakes and conversation. An older woman who has had two sons in prison bemoans her life, asks to have a picture taken with me so she can be famous in America, and boasts of the many children she has, the exact numbers are a bit lost in translation, but what I can gather is that she has 75 children/grandchildren/etc., which seems about right for a place where girls marry young and have large families who do the same.

woman at Jalazone refugee camp, mother of two ex-detainees

woman at Jalazone refugee camp, mother of two ex-detainees

We walk up the stairs to an apartment where the living room is a separately locked room across from the rest of the house and sit in a room with plump stuffed chairs and a shelf lined with certificates, like diplomas or sports awards. But this is Jalazone and these are the certificates of everyone arrested in her family. M. estimates that a very high percentage of the males in the camp have been detained, often the first arrest is as a young boy caught throwing stones or just caught being a young Palestinian boy.

Jalazone refugee camp, certificates of arrest for one family

Jalazone refugee camp, certificates of arrest for one family

We are joined by a woman maybe in her 40s and a large older woman of indeterminate age (everyone looks older than they are) and a buff young man who wanders in and out, smoking. The younger woman has a son arrested one year ago, the older woman lost one son to the IDF and another is imprisoned serving ten long years. The women serve us tea and when I do not drink mine (in my chronically overhydrated state) she urges me to drink, there is no saying no. While the session is in Arabic with a minimal amount of translation, there is a lot of talking and a lot of listening. I watch the body language, the sighing, the gently rocking back and forth, the agitated young man. They discuss the arrests and M. does what he calls narrative therapy, reconstructing their stories which are obviously filled with pain and anguish to find the moments of strength and pride.

The younger woman’s 21 year old son is imprisoned in the Negev, they are allowed to visit monthly though obtaining a permit is difficult. The whole trip starts at 6 am and ends at 9 pm. She spends 45 minutes with her son, staring at him through a glass panel and talking via telephone. No gifts or food are permitted, but they bring shekels for his canteen account. The older woman’s son was first arrested at 23 by the PA, served two years, and then he was arrested by the Israelis while at his home. He is now 28 years old. Hearing that I am a doctor, they ask me about blood donations.

At the second home, two very overweight women sit on a wooden platform with a thin cushion, one is smoking; the room is under construction. Three men are applying concrete, tiling the walls, a woman and a child come in, the men stop to smoke and drink coffee, there is no privacy and a chronic level of chaos. One woman with clearly African features has a son in detention for 30 months, the older woman has a son who is now an ex-detainee. When he was arrested the Israeli soldiers smashed down the door of the house and caused extensive damage. The ex-detainee underwent psychological and vocational training at TRC, but now he sits at home without a job, like many men in the camp. The women are clearly very depressed, there is a general flatness of affect, and M. suspects PTSD though it is hard to be “post” when it is really “ongoing.” It is also clearly impossible to do a session under these conditions. After we leave he reflects on how challenging it is to work with this population, the lack of privacy, the inability to plan visits, it all sounds to me like working with any poor disorganized population who have chaotic, unpredictable lives, an enormous amount of trauma and a mountain of need.

M. decides to visit the mother of a boy paralyzed by an Israeli soldier who shot him in the spine, but the boy is in the hospital in Hebron, so that visit is also cancelled. We wait for the Ford Transit, watching the flood of children getting out of school, often arms draped over each other, with their large Micky Mouse backpacks, some fighting aggressively in little boy ways, one boy kicking an empty box of sanitary pads, (he clearly needs a soccer ball), many yell, “Hi!” and openly stare at me. M. may be the rock star, but I am obviously the stranger and the camp once again has made the decades-long refugee crisis real and urgent for me. I watch the sweet faced little boys parading past and wonder what is their future, do they still dream of anything but a life in the camp, no job, a cycle of arrests and detention, their face on a martyrs poster, what pain and disaster awaits them and when will this end?

poster of young man killed by Israeli soldiers

poster of young man killed by Israeli soldiers

one week ago in Jalazone refugee camp