March 23, 2019

Amman, Jordan

The day begins at The Evangelical Philadelphia Nazarene Church of Marka, a church in Amman that has a particular focus on refugee care. I am told that the number of refugees has doubled since 2010 with mostly Syrians followed by Iraqis (who are classified by the Jordanian government as “guests” rather than refugees). For older data see the UNHCR report here. In the never ending bureaucratic craziness, after 2007 Iraqi children were allowed to go to government schools, but many did not because of displacement due to war (arriving in the middle of the school year, falling behind), confusion over valid residency permits, financial challenges, or the already overburdened public schools. “Many Iraqis still face barriers to education as many families are running out of resources and sending their children out to work, especially in female headed households. In addition, some vulnerable Iraqis are unwilling to register their children at state schools because they do not have legal status in Jordan.”

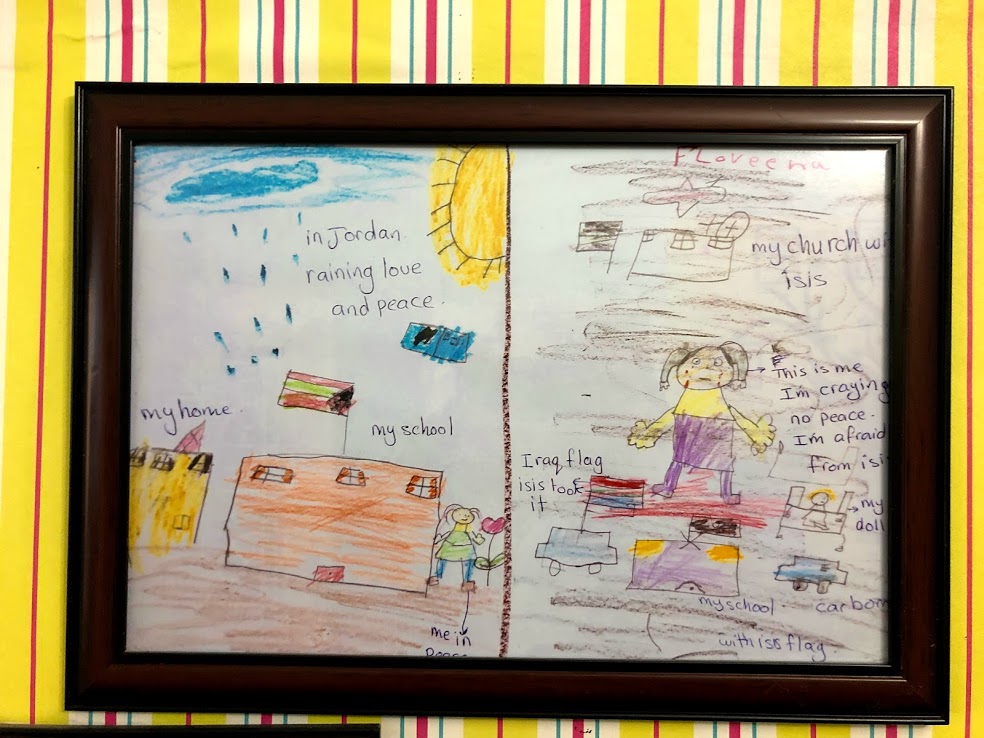

I hear repeatedly, “The Iraqis, they all arrived by plane,” implying they all came with money. It turns out that the Iraqi population that arrived in 2003 was mostly the Muslim white collar class from Baghdad, some with striking wealth who took their gold and built companies and bought residency permits in Jordan. The folks arriving in 2014 were from ISIS controlled areas in northern Iraq and often had only six hours to leave, the announcements arrived at midnight, and the families fled with nothing but their terror and trauma. While religiously diverse, the latter group was an exodus from many historic Christian communities, although the religious breakdowns for the total Iraqi refugee populations are roughly the same from both the 2003 and 2014 communities.

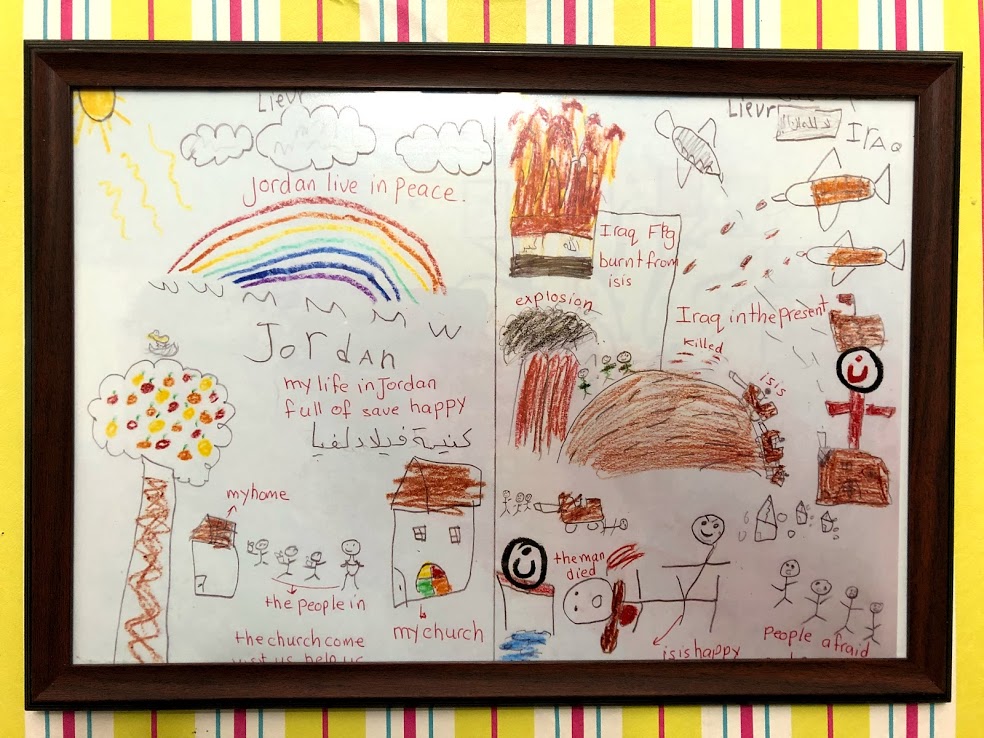

A refugee child’s picture on the wall of the Evangelical Philadelphia Nazarene Church of Marka, in Amman. March 2019. Photo by S. Komarovsky.

I meet an eleven-year-old girl from Mosul who loves to draw, who fled Iraq when ISIS attacked her father and grandfather, severely injuring her father and killing her grandfather for the crime of being Christian. She arrived with her mother, father, brother, and grandmother, shy and quiet, and appears to be a lively, active child with big dreams she is happy to share.

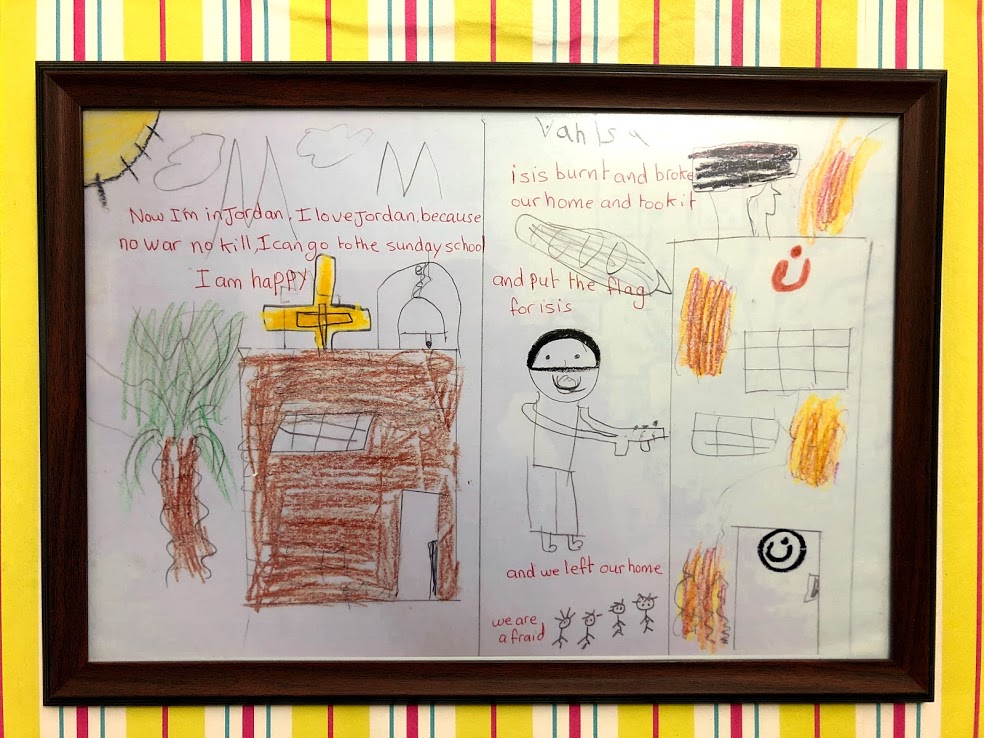

A refugee child’s picture relating ordeal on the wall of the Evangelical Philadelphia Nazarene Church of Marka, in Amman. March 2019. Photo by S. Komarovsky.

Nested in a strong belief in the power of prayer and Christ as the savior, the church built a school that embraces the families (frequently headed by widowed mothers). The parents (who are Assyrian Iraqis and are legally not allowed to work in Jordan) often work at the church as the families wait to leave for Australia, Canada, Sweden and less and less, the US. Thank you, Mr. Trump. The children, who often speak Aramaic, learn Arabic in the Good Shepherd School from ages three to thirteen, Montessori for three- and four-year-olds and then a very progressive curriculum after that. There is lots of drawing, dance, drama, music, science through explorations of the natural world, plus family therapy and home visits. I see a poster picturing zippers, belts, etc., that is used to discuss privacy and staying safe from abuse. Children with developmental disabilities are mainstreamed with extra support.

The Evangelical Philadelphia Nazarene Church of Marka, in Amman. March 2019. Photo by S. Komarovsky.

The church has established an impressive clinic for dentistry, health care, obstetrical care, physical therapy, ophthalmology, and surgical referrals (largely staffed by internationals). Folks work to create welcome packages, food donations, and along with bible studies, there is a Family Day for picnics and games and a Mother’s Day to honor the mothers by making crafts.

I see a quiet area outside with a sandbox, books, and puzzles for children who need some breathing space in the midst of their lessons and traumatic memories. I visit a woodworking project where the Iraqi men develop skills, watch a computer-programmed laser burn designs on olive wood which is sometimes also inset with mosaics. Women (including several completely covered by niqabs) cluster around rows of sewing machines. And then there is the barbershop, beauty salon, soap making rooms, and knitting instruction. The goal is to help refugees become self-sufficient economically.

Talking to staff I learn that Jordan has an estimated two million refugees, that the church provides arrival kits of mattresses, stoves, pillows, and fans. People hear of the program by word of mouth, Muslim refugees cannot attend the school, but the families can use the rest of the services.

Pastor Haytham Mazahreh tells us that the Syrian refugees cannot go back, there is too much loss, fear, the boys may get conscripted; and they are allowed to work in Jordan. There are many NGOs plus USAID and UNRWA providing support. Most of the Syrians are not living in camps. In 2015 there was a sharp cut back in USAID, but the budget was restored the following year. The losses were felt amongst the refugees. I learn that Syrian refugees all walked out of Syria, often for day,s and that 10% are living at the border in 30 unofficial camps, divided by clans, sometimes finding work in the agricultural sector.

The Evangelical Philadelphia Nazarene Church of Marka, in Amman. March 2019. Photo by S. Komarovsky.

The pictures of Syrian families walking from their homes, carrying pillows and belongings, evokes for me the iconic photos of Palestinian expulsions in 1948. I feel my tears rising. How many more refugees will suffer this fate?

The church has also come to the aid of these Syrians, providing physical supports as well as clowns and playgrounds in the desert. Some children die from exposure to harsh desert storms, wind, and cold. Many are too afraid to go to the established camps. “We have nothing, but we do have our dignity.” Forty percent of the women are widows and many refugees have experienced unimaginably severe and chronic trauma from abuse, and at times a repressive culture. Interestingly, violence tends to flare during Ramadan when men are hungry, short tempered, tired, and craving forbidden cigarettes.

A refugee child’s picture describing ISIS atrocities. At the Evangelical Philadelphia Nazarene Church of Marka, in Amman. March 2019. Photo by S. Komarovsky.

I am told that Jordan is also going through its own cultural upheavals. Historically there have been both traditionally conservative and more liberal cultural norms coinciding at the same time. The pastor says that young children are indulged, but there are strict social rules during adolescence, around marriage, travel, and education. Now there are increasingly disparate influences from social media, people are more individualistic. The average age of marriage for men has gone from 28 to 32, but there has also been a sharp increase in both honor killings and child marriages, despite laws to the contrary, a reflection of the increased economic hardships and the influx of refugee populations. Jordan has sharp divisions in wealth, with a third of the country living in poverty, and Iraqi and Syrian refugees facing some of the greatest hardships